Ready for a crisp, empowering primer? You’re about to discover why this art movement still stops people in their tracks! I’ll show you how pared-back forms turn materials into a clear message.

What you see is what you see! In the 1960s artists rejected imitation of the outside world. They made works where the medium and the form are the point. That shift changed how we value objects and how they live in our rooms.

By the end of this piece, you’ll spot essential shapes, read their quiet power, and understand why collectors and creators still flock to these simple forms today. I’ll highlight key artists, explain the term, and give you the confident language to talk about these works with ease!

Key Takeaways

- You’ll learn what defines this bold art style and why it matters now.

- The medium and the form are presented as their own reality.

- Key artists shaped how we see clear, geometric works.

- Simple forms can deliver strong emotional and spatial impact.

- You’ll gain tools to spot and discuss these pieces confidently.

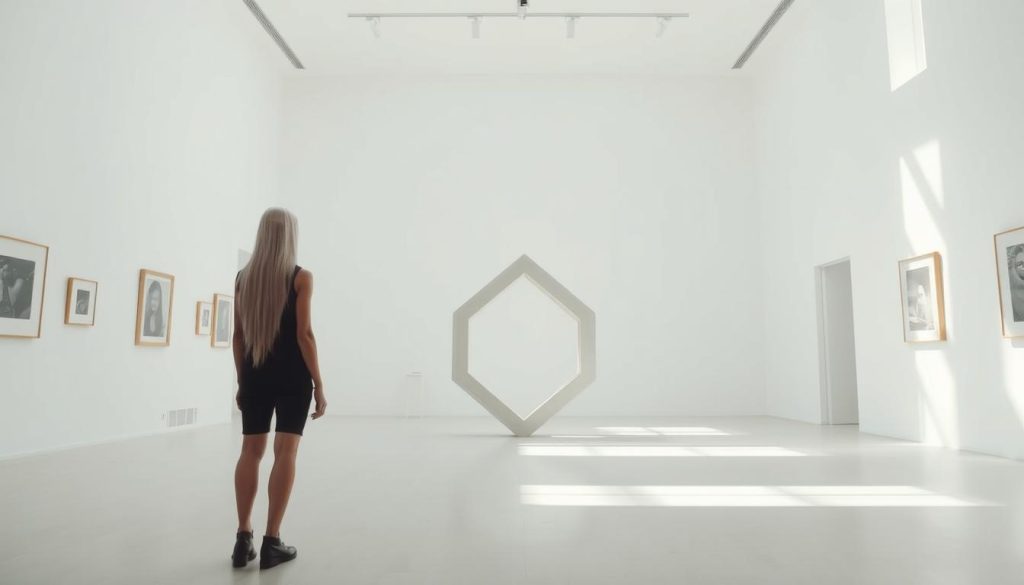

Minimalism Sculpture

At its core, this approach makes the object’s form, scale, and material the message — nothing more is needed! I want you to see the work as a literal presence in space. The medium and the object create their own reality. That idea extends abstraction into a clear, physical language.

Concise definition and scope

Here’s a crisp line you can use: sculpture in this movement is about the literal object before you — its shape, weight, and finish — no narrative required. Artists often used industrial techniques and repeated modules to keep things exact. Frank Stella’s Black Paintings at MoMA in 1959 signaled a shift away from expressive brushwork toward this literal surface and objecthood.

What sets three-dimensional works apart from paintings

Three-dimensional artworks ask you to move. They change your bodily relation to the piece. Paintings, like Stella’s canvases, assert flatness and repetition. Sculpture insists on mass, volume, and the way light and scale alter perception.

- Object first: the work exists as thing, not story.

- Fabrication: industrial processes underline clarity and order.

- Perception: mass and weight make the experience tactile.

Key characteristics: form, materials, and “what you see is what you see”

This movement celebrates clean, measured shapes that speak plainly to your eye! Simple geometry and tight order invite calm. Your gaze rests. The space feels intentional.

Form matters here: squares, stacks, and linear modules set rhythm. Artists like Donald Judd used stacks and progressions to turn a system into a physical language you can walk around and feel.

Material becomes the message. Steel, aluminum, and light are not decoration—they define the work. Robert Morris argued that literal presence and gestalt shape how you sense distance and scale.

Seriality and modular systems create clarity. Repetition guides attention through measured intervals. The result is balance, harmony, and a sense of order that feels honest and steady.

Quick comparison of traits

| Trait | What to look for | Effect on the viewer |

|---|---|---|

| Form | Simple geometric units | Focuses the eye; reduces distraction |

| Material | Honest metals, light, factory finishes | Declares what the object is |

| Systems | Seriality, repetition, modular builds | Creates rhythm and spatial order |

| Structures | Stacks, grids, progressions | Offers balance and clear orientation |

- Read fast: simple forms, honest material, and clear structures.

- Feel it: Judd’s modular logic and Morris’s object focus change how your body moves in front of the piece.

Origins and development in the late 1950s-1970s

A clear pivot in the late 1950s set artists on a course toward measured, factual work! This change favored plain presence over dramatic gesture. It pointed attention to the object’s reality and the rules behind making it.

Turning away from Abstract Expressionism

Frank Stella’s Black Paintings at MoMA in New York in 1959 announced the break. The canvases were flat, factual, and decisive. Painters and makers began to trade lyric brushwork for systems and clear form.

From New York breakthroughs to wider exhibitions

The scene blossomed through the 1960s and into the 1970s with a surge of artworks that valued procedure and module over drama. Key figures like Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Sol LeWitt, Agnes Martin, and Robert Morris shaped that shift.

Over time the movement aligned with conceptual art and reshaped who makes art and how audiences relate to it. Shows in galleries and museums moved these ideas from studios to a broader public. You’ll now see how that era reset priorities and built a new language for modern work!

New York as a hub: studios, galleries, and exhibitions

New York became the engine room where studios, dealers, and curators turned ideas into public moments! You can almost trace a map of change across its neighborhoods.

Key landmarks set the pace. MoMA showed Frank Stella’s Black Paintings in 1959. The Jewish Museum staged Primary Structures (April–June 1966). The Guggenheim ran Systemic Painting in 1966. These shows made an exhibition sensibility visible and urgent.

Critics and curators helped names stick. In 1965 Arts Magazine used the term “Minimal Art” (Robert Wollheim), and that label traveled fast into gallery copy and reviews.

Why it mattered to artists and audiences

- You’ll tour how institutions gave makers space to scale ideas into big displays.

- Neighborhood galleries amplified careers and connected movements to collectors.

- Curators, critics, and artists converged to turn local experiments into lasting talk about art.

So, when you look at a work from this era, place it in New York’s web of studios, shows, and lively debate. That context explains why those pieces still shape how we speak about form and practice today!

Influences from early abstraction and the Russian avant-garde

Early 20th‑century Russian experiments handed later makers a clear blueprint: focus on essential structures and production logic! These movements pushed art toward pure form and repeatable parts.

Constructivism and Suprematism as structural precedents

Artists like Malevich and Rodchenko prized clarity over illusion. Their work stripped composition down to geometry and basic planes. That clarity shows up decades later in the work of many an artist.

Factory techniques and essential systems informing sculptors

Camilla Gray’s 1962 study brought these Russian ideas into English and, over time, into American studios. Makers borrowed factory logic: repeatable parts, standardized joins, and systemized assembly.

- You’ll see Dan Flavin’s homages to Tatlin and Morris’s Notes on Sculpture reference those precursors.

- Donald Judd wrote about Malevich and used modular thinking in practice.

So, when you look at a work now, notice how historic forms and industrial methods form a toolkit. Those systems let sculptors turn past experiments into precise, present‑tense objects you can read easily and enjoy fully!

Notable artists and works often cited

Meet the makers who turned rules into presence! You’ll recognize their names fast in museum labels and catalogs.

Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Carl Andre, Dan Flavin

Donald Judd explored stacks and progressions that make repetition feel calm and precise. His modules create a steady visual cadence you can walk around.

Robert Morris wrote about objecthood and changed how you encounter a piece in space. His essays and works push the viewer to place the object first.

Carl Andre made floor works like 144 Magnesium Square (1969) that invite you to step into the composition. The ground becomes part of the experience.

Dan Flavin used fluorescent light to make industrial light itself a living material. His installations glow like architecture made of color.

Frank Stella, Agnes Martin, and a nod to Eva Hesse

Frank Stella’s Black Paintings and Agnes Martin’s serene grids widened the conversation across painting and three-dimensional work.

Eva Hesse bridged into post‑concerns with a fragile, human edge that kept the dialogue evolving.

- Recognize these names and you’ll spot key works in any show.

- See how each maker treats form, scale, and material differently!

Women in Minimal Art and beyond: correcting the record

The story of the 1960s movement is incomplete without the women who stood at its center! You’ll see how exhibitions and reviews shaped who got credit—and who was left out.

Anne Truitt earned early praise with a 1963 solo at André Emmerich. She was one of three women in Primary Structures at the Jewish Museum in 1966, proving women were already part of the narrative.

Anne Truitt, Jo Baer, Agnes Martin, Carmen Herrera

Jo Baer and Agnes Martin appeared in Systemic Painting at the Guggenheim in 1966. That placement shows these artists shaped how the field looked and felt.

Carmen Herrera made striped canvases in the early 1950s that predate many canonical examples. Her work rewrites origin stories and asks us to rethink priority.

Institutional visibility and gendered historicization

Labels matter. The term “Minimal Art” (1965) and Barbara Rose’s “ABC Art” steered critics and collectors toward certain names. That steering often sidelined women.

Feminist critiques, like Lucy Lippard’s writing (Art Journal, no. 1-2), pushed back. They argued that gatekeeping in museums and reviews blocked fair visibility.

- You’ll meet women whose leadership has been under‑credited—and name the shows that prove it!

- See how exhibitions made or unmade careers in the 1960s.

- Walk away with clearer facts about who was part of the story.

From Minimalism to Post-Minimalism: shifting forms and concerns

In the late 1960s and into the 1970s, makers loosened the strict rules and let materials behave more freely! This change added warmth, chance, and the body back into art.

Eva Hesse, Lynda Benglis, Jackie Winsor and materiality

Eva Hesse pushed fragile media—latex, fiberglass, and rope—into the foreground. Her work accepts change and vulnerability.

Lynda Benglis and Jackie Winsor also embraced tactility. They used sagging, stretching, and visible process to make objects feel alive.

“Eccentric Abstraction” and the rise of organic structures

Lucy Lippard’s Eccentric Abstraction at Fischbach Gallery opened space for intuition and the handmade. That 1966 show is often named as an early turning point.

Critic Robert Pincus‑Witten later coined the term post‑minimalism (Artforum, no. 3, 1971) while writing about eva hesse and related works. He traced how the movement kept clarity but welcomed entropy, chance, and bodily concerns.

| Feature | What changed | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Materials | Latex, fiberglass, hemp | Softness, fragility, visible process |

| Form | Irregular, organic structures | Human scale, tactile appeal |

| Concerns | Body, chance, entropy | Openness and emotional presence |

- You’ll see how artists expanded the language with feeling and pliancy.

- Post‑minimalism keeps discipline but adds poetic ambiguity and warmth!

Materials and fabrication: steel, aluminum, light, and industrial processes

The choice of metal, light, or finish turns every work into a distinct presence in space! You’ll learn why the material is often the message and how makers use it to shape experience.

Corten steel, aluminum tubing, fluorescent light

Corten steel ages beautifully outdoors. Beverly Pepper used it early (from 1964) to give works a weathered, living skin. That patina adds time and strength to public pieces.

Linda Howard favored square aluminum tubing for airy, geometric forms. The tubing makes large structures feel light and walk‑through friendly.

Dan Flavin turned fluorescent tubes into a primary medium. He made light itself a working material and a spatial architect.

Workshop, factory, and the aesthetics of production

Workshop and factory methods bring repeatable precision. Systems and standards create crisp lines and reliable joins. That industrial logic became part of the visual grammar.

“Factory precision gives the work calm and a clear rule to follow.”

- Durability: Corten resists decay and shifts color with time.

- Lightweight scale: Aluminum supports big geometry without heavy bulk.

- Care: Lighting works need maintenance and thoughtful placement.

| Material | Strength | Typical use |

|---|---|---|

| Corten steel | High, weathers to rich tone | Outdoor, enduring public works |

| Aluminum tubing | Light, strong framework | Large modules, walkable structures |

| Fluorescent light | Fragile but radiant | Interior installations; luminous systems |

Think like a collector or curator: material choice affects placement, upkeep, and how the works meet viewers. You’ll spot the logic behind the maker’s decisions and enjoy the clarity it brings to the art!

Forms and structures: squares, rectangles, stacks, and grids

Squares, stacks, and grids act like a spatial grammar that guides your steps and attention! I want you to feel how simple geometry organizes a room. These elements make space readable and calm.

Module-based installations and spatial experience

Artists use repeated modules to set rhythm. Donald Judd’s stacks and Carl Andre’s floor units map a path. Agnes Martin’s grids give steady visual breath.

The placement of a single object changes everything. On the wall it points your sight. On the floor it asks you to move. In a corner it holds a quiet claim.

- You’ll quickly read rooms by spotting stacks, grids, and modules.

- Repeated units create a beat that guides your attention and pace.

- Simple geometry clarifies how works relate to people and space.

See the rules, then enjoy the silence they make! These forms and structures teach you to slow down and really look. You’ll leave galleries with a sharper eye and a fun new vocabulary to describe what you saw!

Viewer experience: objecthood, space, and reality

Stand directly in front of a plain, deliberate object and notice how your body answers it. You’ll feel your pace slow. Your breath changes. This shift is the heart of the experience!

Non-referentiality vs. perception in the gallery and outdoors

Non-referential forms ask you to meet the thing itself. They avoid story so you focus on mass, surface, and scale. Robert Morris called this a gestalt—the whole of object and viewer together.

Outdoors, scale and material intensify reality. Light, wind, and the horizon alter how you sense edges and weight hour by hour. A metal piece gains history as weather works on its skin!

“The object becomes a place you enter with your body and attention.”

- You’ll tune into how your body and breath change around a solid, quiet object.

- Non-referential pieces focus attention on mass, scale, and surface rather than symbols.

- Outdoor placement amplifies reality through shifting light and climate.

- Try this prompt: meet the object, map the space, move slowly, and note changes.

| Setting | What to notice | Effect on experience |

|---|---|---|

| Gallery | Proximity, sightlines, lighting | Controlled perception; subtle shifts in scale |

| Outdoor | Weather, horizon, natural light | Dynamic reality; bodily awareness increases |

| Public plaza | Passage, social use, sound | Interaction and shared experience |

Meet the object, map the space, and let the movement of your body complete the work. That practice deepens your sense of art and the movement that made objecthood central!

Seminal exhibitions and critical terms

Key museum shows in New York anchored the vocabulary critics still use today! They made an exhibition history you can name and use when you talk about these works.

Primary Structures, Systemic Painting, and “ABC Art”

Primary Structures (Jewish Museum, New York, Apr–Jun 1966) and Systemic Painting (Solomon R. Guggenheim, 1966) are anchor exhibitions you should know. They set timelines and put many makers on public view.

“Specific object,” non-intervention, and monochrome essentialism

The term “specific object” and labels like “Minimal Art” (Robert Wollheim, 1965) and Barbara Rose’s “ABC Art” helped critics sort new work into clear piles. That sorting made it easier for collectors, curators, and you to talk about movements and meaning.

- Dan Flavin organized Eleven Artists (1964) and linked light to display and idea.

- Frank Stella and Donald Judd show how exhibitions shape reception.

- Agnes Martin and Jo Baer’s presence widened who counted as part of the story.

- By the 1970s, debates had shifted toward post‑minimal directions with voices like Eva Hesse.

“Exhibitions do more than show work; they name it and make it legible.”

Public space, landscape, and site: expanding the minimalist language

Taking works outdoors changes everything! The sky, weather, and ground become active partners in how you read forms and feel scale.

Beverly Pepper began monumental metal work in 1962 and by 1964 was using Corten steel to let surfaces weather and tell time. Her pieces invite community and sit in parks and plazas as landmarks.

Doris Chase, Jane Manus, and Linda Howard each tested how structures meet urban life. Chase and Lila Katzen focused on social context and placement. Manus welded Corten in the 1970s (Delta One, 1979) and then moved into aluminum, where titles and colours shift perception. Howard’s open-air aluminum forms play with open/closed and straight/curved contrasts to shape movement.

- You’ll see how landscape and light become materials that change with the seasons.

- Works set directly on the ground remove the pedestal and invite physical connection.

- Colours, titles, and siting guide sightlines and shape communal experience.

Practical language helps you evaluate public pieces: check durability, anchor points, sightlines, and maintenance. That way you can talk about how an artwork anchors a place and invites people to gather and reflect!

A clean taxonomy makes searching, cataloging, and collecting feel simple and smart! I want you to read labels like a curator and act with confidence.

Movement and period markers

Movement tags: Minimalism; 1960s–1970s; 20th century. Use these to filter by era and intent. They frame research and help you compare artists and exhibitions.

Medium and support fields

Key tags: sculpture, metal, light, systems. These matter for conservation, display, and transport. They explain how an artwork is made and how it will behave over time.

Themes, forms, and marketplace flags

Themes and tags steer discovery. Use forms, structures, and colours to match visual taste. Add flags like Is unique, Is available, Has chassis, Is framed, Is negociable, Is top seller, Is outdoor to sort inventory fast!

- Size fields: Height, Width, Orientation help plan placement at home or in a venue.

- Catalog keys: Category, Artist, Medium, Support, Movement, Page, Price aid search and curation.

- Thematic tags let you compare artworks across artists and fairs quickly.

| Field | Why it matters | Example values |

|---|---|---|

| Movement / Period | Filters by era and method | 1960s-1970s; 20th century; Minimalism |

| Medium / Support | Guides handling and conservation | Metal; fluorescent light; systems |

| Marketplace flags | Quick buy and display info | Is unique; Is available; Is outdoor |

| Dimensions / Orientation | Ensures fit and sightlines | Height 180 cm; Width 60 cm; Vertical |

Use this glossary to read listings like a pro! It speeds research and helps you compare works across fairs, catalogs, and pages. Go on—try a filter and find art you love!

Collecting Minimalism Sculpture today: what buyers look for

If you want to buy with confidence, focus on provenance, material, and installation needs first! I’ll keep it practical and friendly so you can act with joy.

Unique vs. editioned, outdoor durability, negotiability

Is unique matters. Unique pieces often carry higher value and require clear documentation. Editioned works need numbered certificates and a stated run size.

Check marketplace flags: Is available, Has chassis, Is framed, Is negociable, Is top seller, Is outdoor. These tags save time and reduce surprises!

Materials affect upkeep. Corten steel weathers to a patina. Aluminum resists rust but needs secure anchor points. Fluorescent light pieces need careful electrical planning.

Scale, placement, and condition for exhibitions or homes

Plan for scale early. A work that sings in a New York loft may dominate a suburban garden. Measure sightlines, footing, and service access before purchase.

“Provenance from shows like Primary Structures or Systemic Painting can raise a piece’s market standing.”

Also note condition reports, fabrication quality, and installation needs. Provenance tied to the 1960s and 1970s or links to key sculptors and voices such as eva hesse will broaden the story and value of a purchase. Happy collecting!

Conclusion

Conclusion

You can now see how clear choices in shape and matter changed how people live with art. The movement began in late‑1950s New York and grew through the 1960s–1970s into time‑tested works that still matter today!

Use the landmarks and language shared here to spot forms fast, explain material decisions, and name key exhibitions. You’ll also notice how evolving concerns opened paths into post‑minimal practices and public site work.

Look longer, place smarter, and collect with clarity. One strong piece at a time can change a room and your daily view of beauty and purpose!

Discover the transformative power of authentic healing crystals from Conscious Items, designed to align your spirit and connect you with nature’s energy. With over 500,000 satisfied customers and a 4.9/5 Trust pilot rating, don’t miss out on finding your perfect crystal—shop now before these unique treasures are gone! Take their exclusive crystal quiz today at Conscious Items to uncover your spiritual muse.

If you liked reading this article you will love this article Crystal Healing Properties: Unlock White Crystal Power!

Elevate your spiritual journey with Conscious Items’ genuine gemstones, trusted by thousands and backed by a 30-day money-back guarantee. Don’t let these powerful crystals pass you by—stocks are limited, and the perfect one for you is waiting! Visit Conscious Items now to find your crystal match before it’s too late.

If you liked reading this article you will love this article Minimalism Checklist: The ONLY Checklist you need

Morganite Crystal Healing Properties

Habits of Healthy Relationships: 10 Keys to Lasting Love: The Ultimate Love Stone for Heart Healing